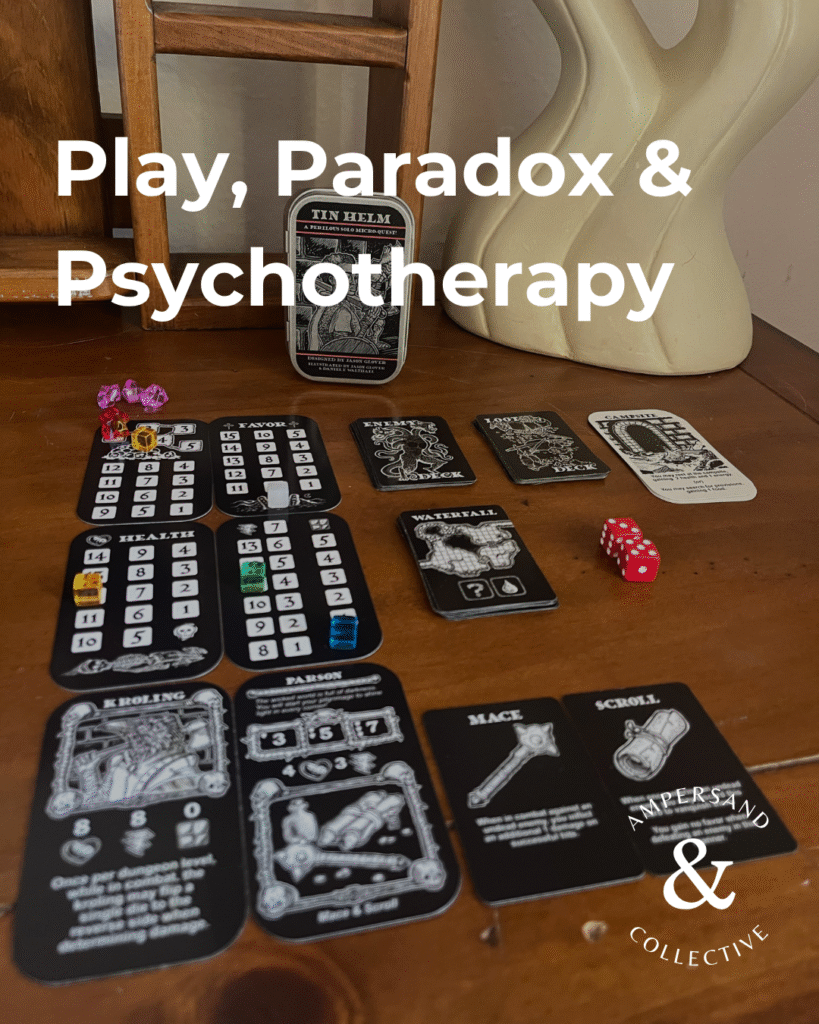

Recently, I’ve been playing the solo board game Tin Helm — a small dungeon crawler that is packaged inside of a mint tin. The game consists of delving into a dungeon in search of three gems, battling monsters along the way. It relies on an interesting mechanic — do I choose to visit the location card in front of me, knowing what will be inside? Or, do I take my chances and flip the next card over, forcing myself to visit an unknown location (possibly facing a monster, finding a gem, or picking up a helpful item)?

What I’ve noticed while playing this game is an interesting dialogue with myself, often weighing various odds and the choices I have available. While some choices may seem obvious, most involve clear risks. Far from making automated actions, the game reveals conflicting desires within me, putting me in touch with different parts of myself that seem to want different goals, despite the game having a clear objective.

Therapy as a Reflective Space to Wonder

Reflecting on Tin Helm reminded me of one of my favorite aspects of talk therapy, which is the potential for it to put each of us in conversation with ourselves. What I mean by this is that psychotherapy, much like Tin Helm and other games, can reflect back to us the different parts and conflicts within us that we may not be able to see on our own, inviting us to see a broader picture of who we are and therefore to wrestle with, contemplate, and accept the various desires and ambivalences found within ourselves. In this way, therapy may at times appear more frustrating than resolving, as we discover that there may be more to us than we initially thought. Of course, the goal is not necessarily to stay in that frustration, but neither is it to run from it.

“Therapy provides a space for us to wonder about the choices we make and the choices we don’t, a space to be curious not just about the feelings we feel but the feelings we don’t.”

As we grow in awareness of and relation to ourselves (perhaps especially to those parts of ourselves that invoke shame, fear, disgust, or other “negative” emotions) we tend to also develop greater ability to genuinely choose — whatever our options may be. Therapy provides a space for us to wonder about the choices we make and the choices we don’t, a space to be curious not just about the feelings we feel but the feelings we don’t.

It is this in-between space that I am drawn to — the space between what we say and what we don’t say, what we do and what we don’t do. Found within that space are conversations about desire, imagination, emotions, and behavior. And I believe much of the therapist’s job is to search for this space amidst the words and silence of a patient, helping individuals to listen to themselves.

When Progress Doesn’t Look Like Progress

To go back to Tin Helm, the game maintains a clear objective; paradoxically, focusing solely on finding the gems may actually make it more difficult to do so. Deciding to battle certain monsters, visit certain locations, and pick up certain items tends to increase one’s chance of success in the game — despite seemingly losing sight of the main objective by focusing on other tasks.

I’ve noticed that therapy can often be the same — patients tend to come to therapy with a particular goal in mind (to resolve a relational issue, to be less anxious, to stop a bad habit, etc.), and objectives and treatment plans are made to meet these goals. Oftentimes, very clear and pragmatic skills and actions prove helpful in meeting particular objectives, and it must be stressed that there are many times in which clear choices can be made (or skills taught) that can immediately improve a patient’s life.

However, there are many times where this is not the case, and therapy may feel more like meandering through the woods than following a clear path. But this is part of my point — maybe the frustration (or enjoyment) that comes with meandering may actually teach us more about ourselves and our goals/objectives than the clear path.

“Maybe the frustration (or enjoyment) that comes with meandering may actually teach us more about ourselves and our goals/objectives than the clear path.”

As the saying goes, it is certainly possible to find ourselves while getting lost. But if we make finding ourselves the point (or losing ourselves, for that matter), we risk missing the gems.

Leave a Reply