Last week, Ann wrote about the therapeutic alliance and why it is important to have a strong relationship of trust and safety in order for psychotherapy to be successful. Building on this “relational fit,” I want to continue the conversation on why your therapist matters by looking at your therapist’s training and theoretical orientation as additional important factors when choosing your therapist.

Not All Therapists Are Created Equally

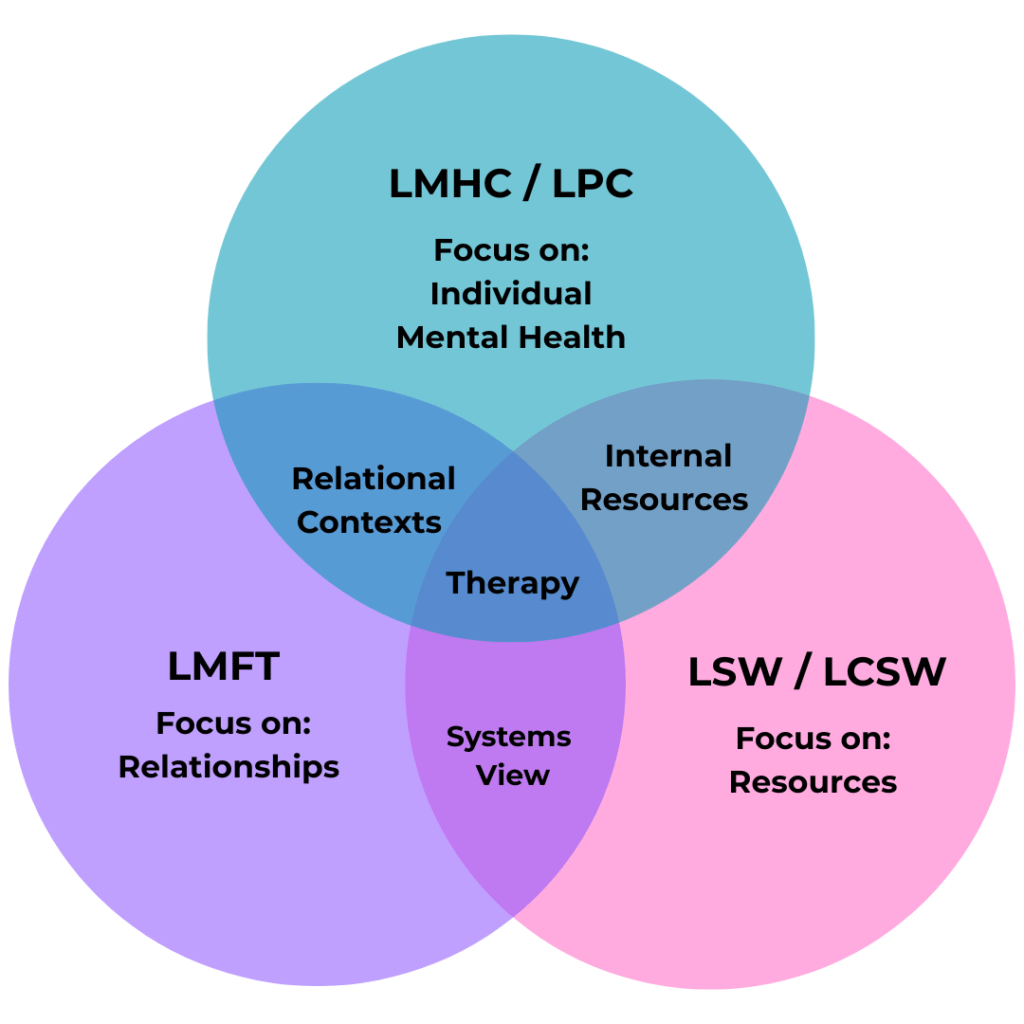

When selecting a therapist, it is important to look at their training as this will set the tone and backdrop for your work together and will likely inform the types of interventions used in your sessions. One way to get a sense of their training is to look at their license type: Are they a social worker (LSW / LCSW) or a marriage and family counselor (LMFT) or a mental health counselor (LMHC or LPC)? Each of these licenses have different trainings that highlight the types of people they work with, shapes the view they have of therapy, and informs the modality or modalities they use within their work. Depending on what you’re hoping to do in and through therapy, finding a therapist that has the training to match your therapeutic desires/needs will be key.

At an overly simplistic view, a licensed social worker (LSW or LCSW) is trained to address someone’s needs within their social and environmental contexts, focusing on a person’s well-being from a systems perspective with a strong emphasis on resources. Often times social workers are looking to connect the person with things outside themselves–does the person have access to medical care, housing, food, work, etc. A licensed marriage and family therapist (LMFT) is trained with a family systems approach, focusing on the relationships within families and long-term committed relationships. As such, someone with an LMFT will often work with couples, families, or a parent-child dyad as a way to help and understand the individual. A licensed mental health counselor (LMHC) or licensed professional counselor (LPC) focuses on the internal world of a person, exploring the emotional and psychological well-being of the person, their mental health. The focus is on helping the individual get to know and understand themselves, as someone who interacts with the outside world. Of course there is much overlap among these three types of therapists including understanding people within their contexts, keeping equity and advocacy in mind, building internal resources, and connecting them to external resources. Therapists with any of these licenses are qualified to conduct individual counseling/therapy, however the experience and goals/outcomes will vary greatly.

What is a Theoretical Orientation?

Your therapist’s theoretical orientation is the way they conceptualize healing and health. It is, in part, an answer to the question: What does health / flourishing look like? Informed by various theories of psychology, a therapist’s theoretical orientation guides the way they engage in the work of therapy. Think of it like a ‘North Star’ or a compass that both shapes their understanding of health and guides how one move towards it.

For me, I fundamentally believe we are made for and by connection. Built on attachment theory (John Bowlby, Mary Ainsworth), British Object Relations (Klein, Winnicott, and others) and interpersonal neurobiology (Dan Siegel), I’ve learned that humans are biologically wired for connection and our early relationships with caregivers shape the way we relate to and engage the people and world around us. Relationships literally change our brains! I could really nerd out here; the research is truly incredible. As deeply relational beings, I believe that health and flourishing are an outflow of being connected to ourselves and others. Some ways we can connect to ourselves are through self-awareness, embodiment and the ability to feel and express our emotions. We can connect to others through vulnerable, authentic and reciprocal relationships. Therefore, my theoretical orientation is a trauma-informed relational psychodynamic approach to therapy. That’s a lot whole lot of pyscho-babble, so let’s unpack that a bit:

- Being trauma-informed means I understand the impacts of trauma on a person’s mental, emotional, physical and spiritual health. Some of the leading voices in trauma that continue to shape my understanding of trauma are:

- Bessel van der Kolk’s pioneering work with veterans helped us understand the long lasting effects of trauma on a person’s physical and mental health.

- Peter Levine & Somatic Experiencing highlight the ways trauma is stored in and processed through the body.

- Hillary McBride’s work around religious trauma and spiritual abuse puts to language to trauma that otherwise feels like a nebulous and all encompassing harm that can not be pin-pointed down.

- Dan Allender and the teaching team at the Allender Center engage childhood sexual abuse and trauma, highlighting the ways our trauma shapes our relationships with ourselves, others and God.

- Being relational means I believe the mechanism for change is found in relationship. Often people need more than new information, they need a new [relational] experience. Here’s a few voices that influence me in the relational realm:

- Gabór Maté posits that people will always choose attachment to others over being authentic to themselves.

- W.D. Fairbairn suggested that humans are motivated by the need for relationships and connection.

- Dan Seigel shows the neurobiology around how are brains are wired for (and by) relationships

- John Bowlby demonstrated how are attachment to our early caregivers shape how we relate to others

- Robin Wall Kimmerer shows the interconnectedness of all things and the need to consider the larger community in a relationship of reciprocity and mutuality.

- Lisa Sharon Harper argues that individual flourishing is tied to communal flourishing and that one doesn’t happen without the other.

- Being psychodynamic means I am looking beyond the ‘surface-level’ of what is happening for an individual to what is deeper: unconscious desires, defense mechanisms, unresolved conflicts. Two of my biggest influences in this arena are:

- Sigmund Freud, the ‘Father of Psychoanalysis’ and the first to conceptualize the mind as having parts that are kept from our conscious awareness.

- Jacques Lacan, a French psychoanalyst who is somewhat lesser known in the states. He continued Freud’s work by looking at linguistics and paying attention to the words people used, highlighting the failure of all communication. We often are saying more than we mean and often are not able to communicate the fullness of our desires.

Stay tuned for next week for Part III where Ann shares her theoretical orientation and how that shapes her work with patients.

📚Resources / Works Cited:

Allender, Dan. Healing the Wounded Heart: The Heartache of Sexual Abuse and the Hope of Transformation.

Allender, Dan and Cathy Loerzel. Redeeming Heartache: How Past Suffering Reveals of our True Calling.

Bowlby, John. Attachment: Attachment and Loss.

Harper, Lisa Sharon. The Very Good Gospel: How Everything Wrong can be Made Right.

Kimmerer, Robin Wall. Braiding Sweet Grass: Indigenous Wisdom, Scientific Knowledge, and the Teaching of

Plants.

Levine, Peter. Waking the Tiger: Healing Trauma.

Maté, Gabor and Daniel Maté. The Myth of Normal: Trauma, Illness and Healing in a Toxic Culture.

McBride, Hillary. Holy Hurt: Understanding Spiritual Trauma and the Process of Healing.

Siegel, Dan.The Developing Mind: How Relationships and the Brain Interact to Shape Who We Are

van der Kolk, Bessel. The Body Keeps the Score.

Yadlin-Gadot, S., & Hadar, A., Lacanian Psychoanalysis: A Contemporary Introduction.

Leave a Reply